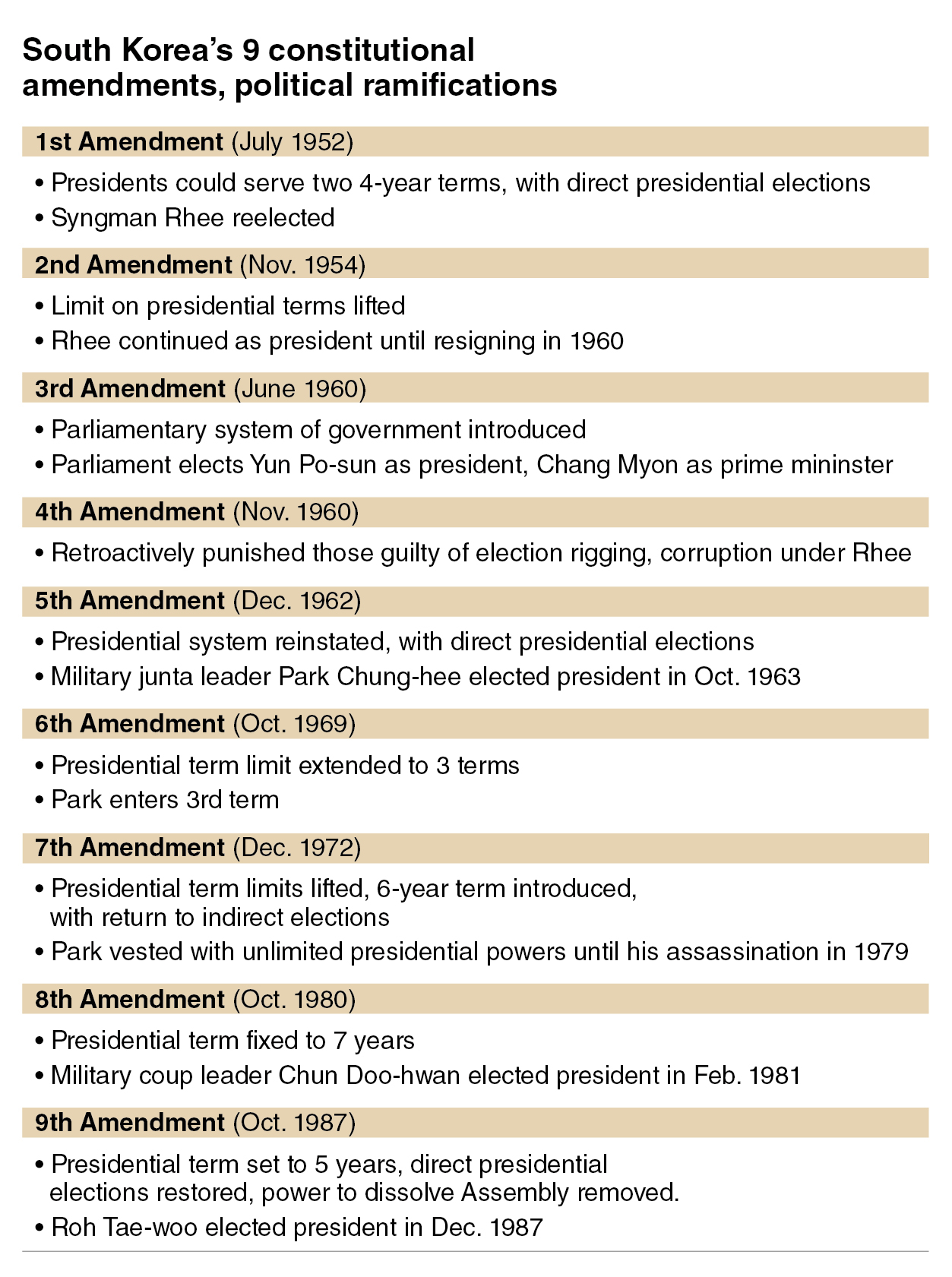

Since the last amendment in 1987, South Korea has struggled with constitutional reform as presidents shy away from curtailing their own power.

It wasn't until she foundered amid mounting corruption scandals that Park Geun-hye proposed an amendment in 2016. The National Assembly did not spend much time wrangling over it before impeaching her instead.

In confirming her removal in early 2017, the Constitutional Court recognized that modern history "gravitated toward concentrating more power to the president," suggesting changes be made to the Constitution to mitigate this.

But eight years on, the Constitution remains unchanged, and another president is awaiting a decision from the same court on his impeachment.

If President Yoon Suk Yeol is removed over his ill-fated martial law declaration in December, will it finally provide the momentum to get reform done? A growing number of people are hoping it will.

Ahead of his impeachment ruling, discussions on constitutional amendment have been spreading across the political spectrum, from conservative blocs to senior statesmen pushing to bring the agenda to the public.

It has become a key points for potential candidates, most of them calling for amendments curtailing presidential power, except for a liberal frontrunner Rep. Lee Jae-myung.

Lee has touched on the need for constitutional amendment but said his party "would prioritize moves to cope with the aftermath of (Yoon's) alleged insurrection" because the debate on the constitutional reform might overshadow his policy priorities.

This was met with criticism from his political opponents.

The ruling People Power Party's Rep. Joo Ho-young, deputy speaker of the National Assembly launched the party's initiative to push for the constitutional reform Tuesday. In doing so, he claimed Lee -- the clear frontronner in early polling for a hypothetical early election -- is merely pursuing his own interests by skirting the calls for the reform.

Han Dong-hoon, the former ruling party leader who has hinted at a potential presidential run, said Wednesday that a constitutional reform must be carried out promptly, adding that the spirit of the Constitution had already broken down.

"Someone must do the dirty work to put an end to the 1987 Constitution," Han said, echoing his previous bid to shrink his presidential term to three years and vowed not to renew his term.

Seoul Mayor Oh Se-hoon, another conservative potential candidate, has also called for the decentralization of presidential power.

Kim Doo-kwan, former Democratic Party lawmaker who is not part of a pro-Lee faction, said Wednesday he would join forces with other liberal presidential hopefuls to persuade Lee to amend the Constitution.

An expert said actions taken by opposition leader Lee's rivals in the potential presidential race should be seen as a strategic approach, as recent polls have shown that Lee is far ahead in the presidential race prediction.

"If these rivals had high odds of winning, they wouldn't have preemptively proposed a shorter presidential term," said Yoon Kwang-il, professor of political science at Sookmyung Women's University.

He added that the conservative candidates' promise will remain hollow unless it secures the liberal Democratic Party's cooperation, because a referendum for the amendment requires at least a two-thirds majority in the Assembly, where Democratic Party lawmakers hold 170 seats out of 300.

Meanwhile, a recent poll by Research View on Wednesday indicated that nearly 6 in 10 respondents opposed the constitutional reform aimed at reducing the presidential term to three years should the early election take place in May. Among those identified as supporters of opposition leader Lee, over 70 percent of respondents were against the reform, the poll suggested.

Political elders step up

On Wednesday, Chyung Dai-chul, chair of the Parliamentarian's Society of the Republic of Korea, said a constitutional amendment to curb presidential power must precede the presidential election.

Without the timely amendment to the Constitution, any irregularities by a sitting president could resurface at any time, further aggravating the political bipolarization already rampant in the society.

"The lesson we learned from (President Yoon's) martial law imposition is that an ordinary president could abruptly turn into an imperial president," said Chyung, who was a five-term lawmaker until 2004, at Seoul Station during his campaign for reform. "The same thing could happen for whoever gets elected in the next presidential election."

A dozen former political heavyweights recently gathered to discuss ways to curb presidential power, suggesting a parliamentary democracy or a semi-presidential system as alternatives.

While the heavyweights differed over their priority in pursuing the constitutional change, they consented that the time is ripe for the reform in hopes that a presidential election and a legislative election could take place simultaneously beginning in 2028.

At a forum hosted by Institute for Future Strategy at Seoul National University on Tuesday, Park Byeong-seung, former six-term lawmaker who served as the National Assembly speaker from 2020 to 2022, called on South Korea to adopt a semi-presidential system, through which a president independent of a parliament exists while some of their power is delegated to the prime minister.

"My hope is South Korea's transition to a semi-presidential system," he said, adding it is imperative that the presidential term be shortened to three years for President Yoon's successor, elected in an early presidential election. He added that Yoon's successors should be allowed to renew a fixed four-year term once.

Kim Jin-pyo, former National Assembly Speaker, resonated with former lawmaker Park by saying there is "no other feasible way" than adopting the dual executive system due to people's lack of trust in the parliament and the time constraint.

However, Kim Hwang-sik, former prime minister from 2010 to 2013, said a semi-presidential system might confuse South Korean politics, given that executive power might go to a prime minister whom people never vote for, unlike the president elected through a popular votes.

Chung Un-chan, former prime minister from 2009 to 2010, claimed the parliamentary system — which was in place in 1960 but was short-lived due to Park Chung-hee's military junta — could be reinstated in South Korea, given people's enhanced democratic engagement and their level of political awareness.

consnow@heraldcorp.com